Disclaimer:

This article is published by 2Firsts with the author’s permission. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of 2Firsts.

Key Points

1. Tobacco Price Elasticity (TPE) is overly simplistic:

While widely promoted as a tool to reduce smoking, TPE reduces a complex issue of nicotine dependence to a basic price-consumption equation, ignoring psychological, social and structural factors.

2. High tobacco taxes have unintended consequences:

In countries like Australia and across Europe, elevated taxes have led to thriving black markets, increased criminal activity, and significant tax revenue losses – without proportionate health gains.

3. The most vulnerable populations are hardest hit:

Low-income individuals and people with mental health disorders, who are least able to quit, face rising living costs and social stigma, while governments rarely reinvest tobacco tax revenues into cessation support.

4. Fiscal motivations often override health goals:

In times of economic distress, governments rely on the inelastic nature of tobacco demand to generate stable revenue, effectively monetizing dependence and undermining the public health rationale.

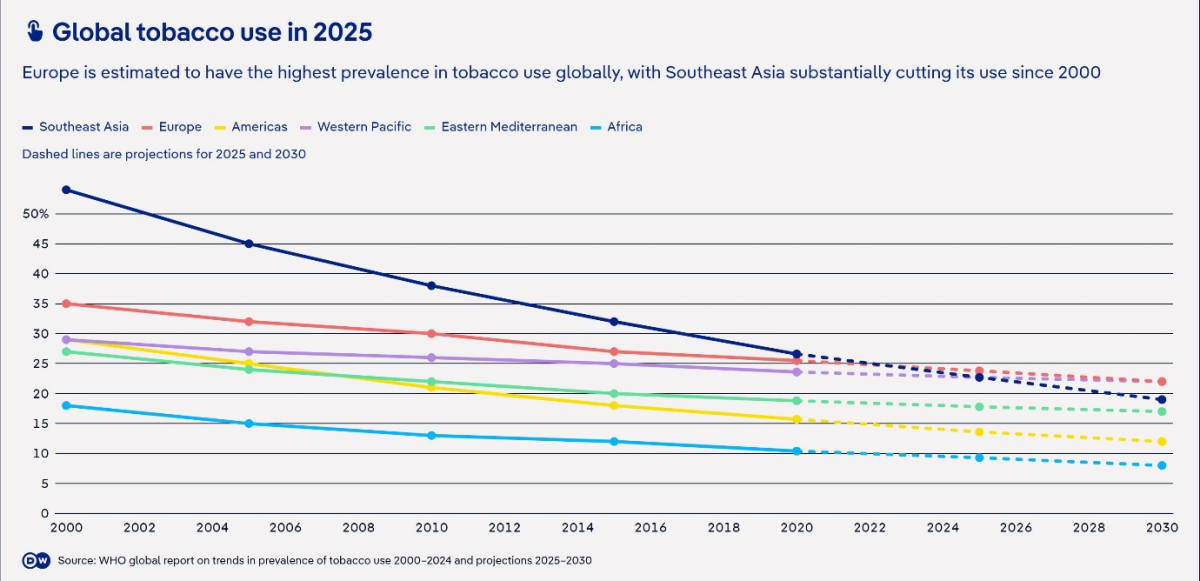

5. Global smoking reduction is stagnating:

Despite aggressive tax policies, smoking prevalence has declined by just 0.46% annually since 2000. Without a shift toward harm reduction and reinvestment in quit support, an estimated 300 million people—mainly in poorer nations—will die from tobacco-related diseases.

Tobacco Price Elasticity: A Convenient Myth?

The policy's limits are defined by a nation's economic needs, shifting between a health argument in good times and a revenue tool in bad.

Samrat Chowdhery

A nicotine policy expert based in Mumbai, India

Raising tobacco taxes is championed by global health bodies like the World Health Organisation as ‘the single most effective tool to reduce smoking’. The policy rests on the economic principle of Tobacco Price Elasticity (TPE), which suggests that as prices rise, consumption falls. Seminal studies and consensus estimates place this elasticity at around -0.4 for high-income nations (a 10% price increase leads to a 4% consumption drop) and as high as -0.8 in developing countries.

The result is a policy narrative that is simple, powerful and politically appealing: that a single lever (price) can simultaneously achieve public health goals, generate state revenue and advance social equity. Perhaps the most crucial element of this framework is that it is justified as a "pro-poor" intervention, arguing that lower-income groups are more price-sensitive and therefore more likely to quit, reaping the greatest health benefits.

The simplicity of this narrative however masks profound underlying complexities and contradictions. By framing a complex biopsychosocial issue like nicotine use primarily in economic terms, health activists have transformed the lived experience of dependency into a straightforward calculation of price and quantity.

This monetization of dependence, under the guise of public health, ignores the social contexts of smoking, the lack of viable alternatives for many individuals, unintended behavioural adaptations and the emergence of powerful countervailing market forces – failures that evidence from around the world makes starkly clear.

A key admission health groups fail to make: When this policy is pushed to its limits through repeated, steep tax increases, people who smoke cigarettes do not simply stop. Instead, they adapt.

How effective has the policy been?

In Australia, which boasts some of the world's highest tobacco taxes, the policy’s effectiveness has diminished. While smoking rates have declined, this trend is not solely attributable to tax increases, as rates have also fallen during periods without significant hikes suggesting that broader shifts in social attitudes, cultural norms and other policies like smoke-free area laws have played a substantial, if not primary, role in reducing prevalence.

A fallout of such high taxation is also the creation of a massive illicit tobacco market, which accounted for a 14.3% "tax gap" in 2022-23, representing $2.7 billion in lost revenue and directly subverting public health goals by forcing users towards cheap, unregulated alternatives. Moreover, as of August 2025, Australia has witnessed over 250 firebombing of tobacconists. When the tax component of a legal pack of cigarettes exceeds 80-90% of the retail price, it creates an enormous profit incentive for criminal networks.

Similarly, despite having among the highest tobacco taxes, the latest WHO data shows Europe has become the smokiest place on Earth, at 26% of the adult population lighting up, including a staggering 29% of young Europeans aged 15-24. High prices have driven consumers to cheaper products like roll-your-own tobacco or the illicit market, which cost European governments an estimated €11.6 billion in lost tax revenue in 2023.

Despite these failures however, the European Union is set to increase taxes further by revising the Tobacco Taxation Directive, which if fully implemented, is expected to raise an additional $15 billion in revenue. This will most likely accrue to poorer eastern states which are still heavily reliant on tobacco tax and provide further boost to organised crime, even as major economies like the Netherlands are already reporting tobacco tax hikes are not generating any extra revenue.

The revised measure not only proposes to double excise duty on already unaffordable cigarettes, but also widens its scope to significantly tax novel, and safer, nicotine alternatives such as e-cigarettes, heated tobacco and nicotine pouches, with the misguided aim to prevent product substitution. This shows the true failure of any health basis to the tax – it is like throwing more petrol on a burning theatre while barring the exits.

Penalising the most vulnerable

The most damaging impact of such measures is felt by marginalised low income people who can’t ‘just say no’ and thus have affordability challenges for life necessities, in addition to the stigma foisted on them for continued smoking, all added to the huge burdens so many of them already face.

Among them are also people with mental health disorders such as ADHD and schizophrenia who have very high rates of cigarette smoking, and there is evidence that this is self-dosing to treat their symptoms, so they are quite unlikely to be able to stop using nicotine. They are also generally hugely financially disadvantaged. Putting up the price of cigarettes without providing viable alternatives removes food, clothing, housing and other necessities rather than cigarettes from their expenditures.

Meanwhile, the rise of black market directly sabotages the policy's twin goals. First, it negates the public health objective by flooding the market with cheap alternatives, worsening overall public health and making it easier for young people to start smoking and harder for existing smokers to quit. Second, it decimates government revenue. Every illicit pack sold is a pack on which no tax is collected, leading to billions in lost funds. The policy, designed to generate income, ironically ends up funding organized crime.

Monetizing dependence in downturns

Times of economic distress truly reveal the policy's twisted logic. The public health argument relies on demand being elastic – that people will quit. The fiscal argument, however, relies on demand being inelastic – that most dependent users will simply absorb the cost, guaranteeing a stable revenue stream for the state.

The fiscal imperative became most evident during the post-pandemic recovery. In the past few years, numerous countries have implemented tobacco tax hikes – a staggering over 35 nations raised tobacco taxes in 2022-23 when global inflation was at its highest in over three decades – ostensibly to shore up government finances, exploiting the addictive nature of the product for predictable revenue. This transforms tobacco from a public health crisis into a strategic fiscal asset.

Lost in these macroeconomic calculations is the dependent consumer, who is punished financially but offered little assistance. The most damning evidence of this policy's true intent is the systemic failure to reinvest the tax windfall into smoking cessation programs and facilitating transition to far less hazardous alternatives.

A broken contract

According to WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2023, in 2020, governments collected $367 billion from tobacco excise taxes, but spent mere $1.63 billion on tobacco control, a paltry 0.44%. More alarmingly, almost 85-90% of this expenditure was in high-income countries and not in developing nations where 80% of smokers live.

In India, for instance, while collecting over $9 billion in tobacco taxes, the government allocates less than 0.07% of this revenue to its National Tobacco Control Programme, even of which 70% remains unutilised. This broken ethical contract exposes the tax not as a health measure, but as a regressive levy that extracts wealth from a vulnerable population to fund general state expenditures.

The concept of TPE may not be a myth in itself – there exists evidence that taxation reduced smoking in the 1970s and 1980s when smoking rates were high in high-income nations and many people quit, especially after the first reports about tobacco harms became publicly known – but its application as a cure-all for tobacco dependence is. The policy's limits are defined by a nation's economic needs, shifting between a health argument in good times and a revenue tool in bad. It has become a convenient justification for monetizing dependence.

Heath taxes: Bad to worse

Undeterred by the mixed to failed results in the tobacco arena, the WHO has recently proposed to cast the net wider by proposing to raise “heath taxes” on a wide range of sin goods from sugary drinks to alcohol which will inevitably lead to similar results, including expansion of organised crime and black markets while disproportionately impacting the poor.

A truly effective strategy must move beyond this one-dimensional approach, balancing taxation with legally mandated reinvestment in cessation support and providing tobacco users access to a bouquet of quit pathways, including switching to harm reduction alternatives through differential and risk-proportionate taxation, and a serious commitment to combating the illicit trade that high taxes inevitably create.

Without this, tobacco taxation will remain a cynical fiscal policy masquerading as a public health intervention.

A Grim Forecast

Apart from WHO’s marquee tax hike measure, its other tobacco control policies in MPOWER have also shown meagre results, which demands a fresh approach than doubling down on ineffective strategies during WHO’s upcoming global tobacco conference, FCTC COP11. Since 2000, degrowth in smoking prevalence has been mere 0.46% per year, at which rate it will take at least another 32 years to bring prevalence down to under 5%. An estimated 300 million people, mostly in poor nations, will die from tobacco-related illnesses in this period.

The author is a nicotine policy expert based in Mumbai, India; With inputs from Prof David Sweanor, Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa