In 2019, there were more than 18.5 million menthol cigarette smokers ages 12 and older in the U.S., according to the FDA.

Tobacco is the leading preventable cause of disease and death in the United States, causing more than 480,000 deaths each year, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Among the different tobacco products, smoking menthol cigarettes is the most harmful. It is also disproportionately smoked by Black Americans, which traces back to the product’s targeting from its early years. The gap is apparent – 85% of Black and African American cigarette smokers use menthol cigarettes compared to 29% of white cigarette smokers.

University of Minnesota professor Dana Mowls Carroll and other researchers recently highlighted inequities in product regulations between e-cigarettes and menthol cigarettes. Their goal was to emphasize the importance of centering people of color, specifically Black and Indigenous communities, in menthol cigarette research so the FDA can create policies that positively impact the communities affected.

“Twenty-one percent of the research that’s done to inform the Food and Drug Administration is among populations that are Black and African American or indigenous. That’s, to me, problematic,” Carroll said. “The populations that are most impacted by smoking should really be centered at the efforts of the Food and Drug Administration.”

Effects of menthol

Menthol is a flavor additive with a minty taste that reduces the irritation and harshness of smoking while enhancing nicotine’s addictive effects. As a result, there’s a high likelihood that youth who smoke menthol cigarettes will continue to use regularly and have a harder time quitting. In 2019, there were more than 18.5 million menthol cigarette smokers ages 12 and older in the U.S., according to the FDA.

“Cigarettes are the deadliest product sold legally in the United States. I mean, there’s nothing like a cigarette,” Carroll said. “It combusts and burns. Because of that, it delivers thousands of chemicals. We know about over 70 are carcinogenic.”

Exploiting a government policy in place since the late 1800s that outlawed the use of traditional Native communities’ tobacco products, commercial tobacco targeted Indigenous communities with various marketing tactics. That policy remained until 1978. In Minnesota, 59% of Native American adults smoke commercial tobacco, compared to 14.5% of Minnesota’s overall adult population, according to the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH).

Carroll said it’s important to consider the history of targeting when looking at the rates of populations who smoke.

“I always cringe when I see studies that say something like, ‘Fifty percent of American Indian(s) smoke cigarettes’ and leave it at that as though individuals have chosen to do these unhealthy behaviors, but really it’s this historical structural issues that have resulted in these high smoking prevalence,” Carroll said.

Menthol targeting of Black communities began around the 1950s, according to Eugene Nichols, a board member of the Association For Non-Smokers in Minnesota (ANSR).

“I remember as a young child growing up in the ‘60s, looking at magazines that were targeting the Black community, like Ebony and Jet Magazine. The ads in there were focused on Black smokers and how happy they would be,” Nichols said.

Nichol’s recalled the tobacco industry would give out free menthol cigarettes in Harlem.

“My brother started smoking at the age of 15 because the vans would be parked strategically on 125th Street,” he said. “The kids would know to go get ’em. That’s where my brother started smoking, who incidentally has passed away of COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) because of his smoking addiction.”

The impact of that targeting is present to this day, Nichols said.

“If you take a look at the health statistics of African Americans nationwide, we die from COPD, high blood pressure, certain cancers, especially lung cancer that is specifically tied to the use of nicotine smoking,” he said.

On top of that, the menthol helps the nicotine go down smoothly, which is why it became such a favorite among most who smoked it. Based on a 2017 survey ANSR conducted, menthol cigarettes take five to six more quit attempts than other cigarettes.

“The history is clear, the numbers are clear, the health data is there. Black people in specific have issues that are related directly to smoking more than any other race, and hence you have a disparity in health, specifically in Minnesota,” Nichols said.

Inequities in federal response?

In June, the FDA ordered the e-cigarette company Juul to remove its electronic cigarettes from the U.S. market. In early July, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit granted Juul’s request for a hold on the ban while the court reviews the case.

Nonetheless, the FDA took action.

Carroll attributes the restriction policies for e-cigarettes to the fact that the products were impacting white youth specifically.

E-cigarette use is most common among white youth, with 32.4% of white high school-aged youth reporting e-cigarette use compared to 23.2% of Hispanic and 17.7% of Black, according to the 2019 National Youth Tobacco Survey.

“What we say in this commentary is that we agree that youth prevention of e-cigarettes is a priority, but the urgency that it received, because the users were white, just was far more than the urgency of that menthol cigarettes has gotten,” Carroll said. “I think it just reflects the legacy of racism and who is being prioritized.”

Nichols said while the policy difference could be racial, most politicians have taken a strong stance against vaping because of its danger to the development of youth. He agrees, however, that the FDA should have done more to restrict menthol cigarettes.

“They had an opportunity to do it in 2009. And here we are now in 2022,” he said. “Is it racist? You know, more Black people use it; one might consider that. And if you talk to some Black people like (the) Rev. Al Sharpton, he thinks he’s racist that we’re trying to ban the use of menthol.”

Nichols thinks there’s a form of race-related influence behind the difference in the government response, but he believes it’s more about economic gain.

“They’re putting profit over health, and in a country like the United States, which is certainly an economically driven country, we respect profit. That’s what’s happening,” he said. “It’s gonna be a really difficult thing to get anybody to say, X, Y, Z companies should not be allowed to make a profit, and we’ll turn our eyes away from the fact that they’re killing people. That’s the despicable thing about it to me.”

In April, the FDA announced it would implement a plan to curb menthol cigarette sales. Public commentary on the proposal is accepted until August.

The menthol epidemic is ongoing, and each year that menthol stays on the market, more young people will get addicted, and the health inequities will grow, said Emily Anderson, director of policy for ANSR.

“Anything that leaves out menthol is an inequitable policy when it comes to the racial health disparities,” Anderson said. “With that said, we have seen some cities only want to address vaping and e-cigarette products and not want to address menthol cigarettes. That, I would say, definitely does not have a public health rationale, but in their minds, it has a political rationale, a business rationale. The money maker for the tobacco industry is still menthol cigarettes at the end of the day.”

Minnesota’s stands on menthol

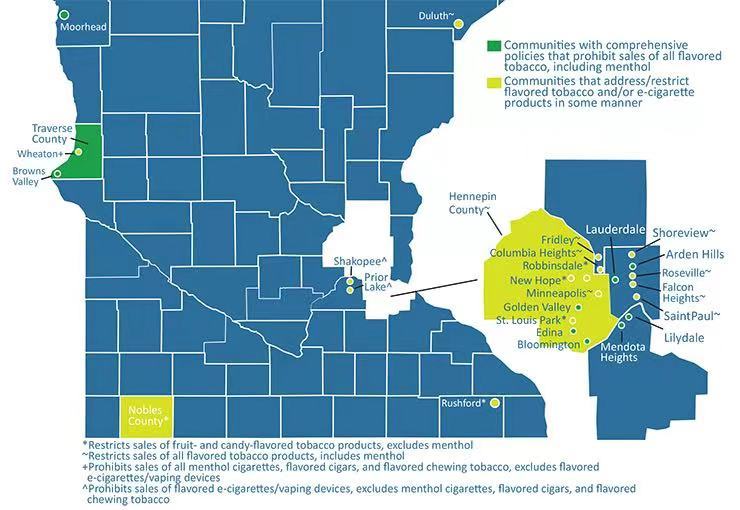

There is currently no state-wide legislation prohibiting menthol tobacco, although ANSR is working on a bill for the next legislative session.

The bill, sponsored by Cedrick Frazier (DFL-New Hope), aims to end the sale of all flavors, including menthol, in the state.

It has bipartisan support in the House but did not get a committee hearing in the Senate. Anderson hopes it will be brought back up next legislative session, depending on Senate leadership.

In 2015 and 2016, Minneapolis and St. Paul restricted fruit and candy-flavored tobacco products to adult-only stores and set a minimum price for cheap, flavored cigars.

In 2017, with support from the Minnesota Menthol Coalition, Minneapolis and St. Paul added menthol to their flavored tobacco restriction, making it so menthol-flavored tobacco products can only be sold in adult-only tobacco stores and liquor stores.

“It was really that stair-step approach, both from a politics perspective, as well as a community organizing perspective. I think the latter of which is probably where we put blood, sweat and tears and just knew that it how important it was to have buy-in,” Anderson said.

Nichols recalled the reaction of one St. Paul store owner during a city meeting on the menthol restriction.

“He was testifying. He took the keys out of his pocket and dramatically threw them up on the podium and said, ‘If you restrict the sale of menthol, you may as well just take my home and take my life,'” Nichols said.

The policy does not entirely prohibit the sale of the items. Instead, it restricts them to only being available at adult-only tobacco shops, which require 90% of their revenue to come from tobacco-related products. Both cities implemented the policy in 2018.

Several other cities have also passed menthol restrictions, including Edina, Bloomington, Arden Hills, Mendota Heights and Golden Valley, among others.

Minnesota communities addressing the sale of flavored commercial tobacco products

Nichols thinks local legislation, started through educating local governments on the issue, is the best place to start advocacy. It also helps to have someone from the community that you’re reaching out to be an advocate.

Anderson said a common fear of people is being perceived as racist for taking a side on restricting menthol.

“The onus is on the industry for creating this issue. And now, we’re trying to clean up a mess that they’ve created. That’s why it’s so important to have these types of policies come from Black leaders, from Black organizations and from Black coalitions. Because it has to be the people that are impacted doing the leading,” Anderson said.

NorthPoint Health & Wellness Center in North Minneapolis has a team focused on supporting local policies that seek to restrict sales of all tobacco products, including menthol.

“The policies that we’ve supported in the past have really focused on the African American community and education around that as well through presentations and just meeting with community members about how marketed targeted of menthol tobacco has really impacted the African American community,” said Bethlehem Yewhalawork, the program manager for Health Policy & Advocacy at NorthPoint.

NorthPoint does educational outreach around vaping and menthol cigarettes, primarily at Minneapolis schools. The organization makes it a point to educate youth about the danger of menthol because it masks the harshness of smoking and makes it easier to be addicted.

“We see that a lot of these kids are being impacted by vaping, but what about the other communities that have been impacted by menthol tobacco for all these years? We really make it a point to include menthol and all of our flavor tobacco restrictions because we understand the disparities that are caused by menthol tobacco,” Yewhalawork said.

The content excerpted or reproduced in this article comes from a third-party, and the copyright belongs to the original media and author. If any infringement is found, please contact us to delete it. Any entity or individual wishing to forward the information, please contact the author and refrain from forwarding directly from here.